By Cathy Moore

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

“Wait, we can’t design the training that way, because Zeus will rain down fire as punishment!”

You might not hear that particular myth, but I’ll bet you’ve heard many others. Here are the most popular myths I’ve heard from learning designers and their clients.

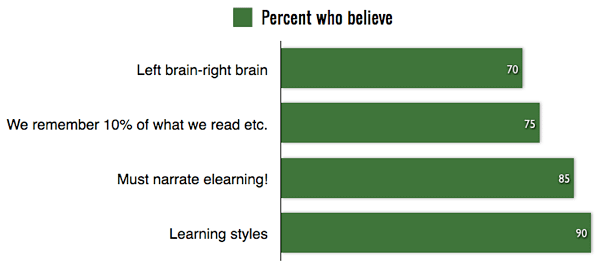

Oh, those numbers in the chart? They’re just an estimate based on my experience. They’re not real.

They’re like the numbers that someone tacked onto a graphic created by Edgar Dale, magically turning it into a “scientific” and unfortunately misleading “truth” about how much we remember, as Will Thalheimer thoroughly shows.

Putting science-y numbers on concepts is just one part of a larger problem we face: We let unfounded beliefs influence us.

It’s a cultural problem

Why do myths flourish in our supposedly science-based profession?

I like to use a flowchart to analyze performance problems. If we were to use the flowchart to answer “Why do training designers make decisions based on myths?” I think we’d find that the main problem is an environmental one:

We work in organizations that believe harmful myths. We’re pressured to work as if the myths are true, and we can’t or don’t take the time we need to keep our knowledge up to date and combat the myths.

Stand up to the client

We need to change this cultural problem, and one of the first steps is to politely stand up to the client who believes in the impending punishment of Zeus. “I understand your concern,” we might say. “Luckily, research shows that Zeus doesn’t actually exist and has no opinion about our training.” We back this up with a link to an easy-to-read summary of research showing the non-existence of Zeus.

For example, let’s say we have a client who believes in learning styles.

“Learning styles are real,” they say, “and we must design the training to accommodate them.” This has been debunked repeatedly yet stubbornly lives on. It’s one of the most common excuses for inflicting slow narration on elearning users. What can help us debunk this?

- This PopSci article is a quick, entertaining read and could be a good one to send to the client.

- Learning styles: Worth our time? links to two major debunking studies and highlights techniques that work better. It might appeal more to learning geeks.

- Here’s an excellent roundup of opinions from L&D luminaries, from Guy Wallace. It might help convince people who need to see that many experts argue against learning styles.

It’s also helpful to dip into research compilations in our spare moments. For example, the extensive PDF report Learning to Think, Learning to Learn organizes research into specific, plain-English recommendations that are easy to read in short bursts. It’s aimed at people who teach remedial courses but applies to all types of adult learning design.

For research specific to elearning, I always recommend e-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning by Ruth Clark and Richard Mayer.

Expose myths to the sun

Another way to weaken myths is to clearly state them, to bring them into the light and ask stakeholders, “Is this really true?”

For example, here are some beliefs that affect our ability to design effective training. What would happen if we had our stakeholders stop and consider whether they’re actually true?

- If there’s a performance problem, training must be the solution.

- Training is a one-time event or course.

- Training means putting information into people’s heads.

- Our job is to make this information easy to understand and remember.

- We should first tell people what they need to know, and then give them an activity so they can check their knowledge.

- We shouldn’t let learners make mistakes because that would demoralize them and they’ll only remember the mistakes.

- We shouldn’t let people skip stuff they already know because they probably don’t really know it.

- We should measure learning with an assessment right after the training.

- If we’re designing elearning, it should look like a slide show. No one will learn from a normal web page with scrolling.

- If we’re designing elearning, we should have a narrator talk through the slides because no one will read.

I could go on (and on!) but you get the idea. A lot of assumptions drive what we do, and we need to clearly identify and question them before they steer us in the wrong direction.

What are the most damaging or stubborn myths that you’ve seen? Have you been able to fight them effectively? Let us know in the comments!

Scenario design toolkit now available

Design challenging scenarios your learners love

- Get the insight you need from the subject matter expert

- Create mini-scenarios and branching scenarios for any format (live or elearning)

It's not just another course!

- Self-paced toolkit, no scheduling hassles

- Interactive decision tools you'll use on your job

- Far more in depth than a live course -- let's really geek out on scenarios!

- Use it to make decisions for any project, with lifetime access

Hi Cathy, loving your work!

The 4th bullet point in your list of faulty assumptions has me a little puzzled… “Our job is to make this information easy to understand and remember.” Not sure if I’m missing something here. When designing training with a knowledge based element I would always seek to present that information in an easy to understand/remember type of format – maybe a visual one, for example. Can you advise what you see to be the fault in this please? I’m not getting it.

Thanks very much,

Martine.

Martine, thanks for your comment. I should have added “only” to that 4th bullet point, to say, “Our only job is to make this information easy to understand and remember.”

My concern is that training designers and clients often assume that the performance problem comes from a lack of knowledge. The next logical conclusion is that putting information into people’s heads will solve the problem. Then the training design becomes simple information design followed by a knowledge check.

I’m also concerned that much of the training design advice we see focuses on designing content for “engagement,” memorization, and short-term retrieval on a quiz. While there are certainly many fields in which a lot of information has to be memorized, such as medicine, I’ve seen many projects in which memorization isn’t necessary. In these projects, people should be helped to analyze a problem and apply useful strategies, not just memorize information. For example, in ethics training, people should be challenged repeatedly to make ethical decisions in a wide variety of situations, not just presented with a list of do’s and don’ts to memorize.

So that fourth bullet point refers to the assumption that training design is simply information design, and not, for example, experience design or the design of realistic decision-making activities.

Dear Cathy,

again a very good article about learning myths and other common sense nonsense,thanks.

There are two big review research projects about effective teaching and learning: Hattie and Marzano.

I saw the Huge bible from the Hattie research in a bookshop in London.. to heavy for my plane home.

But I saw also a very handy summary from Marzano and Hattie written by Geoff Patty about evidence based teaching. In combination with the book from Clarke & Meyers (third edition!) I advice people to read these two books. See: http://geoffpetty.com/geoffs-books/evidence-based-teaching-ebt/

Ger, thanks for the link!

Thanks for this article, Cathy. Just curious what you think about the 70-20-10 phenomenon. Does that also merit comment?

Thanks for another brilliant posting! I once had the audacity to ask where the much touted 70-20-10 came from and got an earful but no answer. I began to realize that these myths are kept alive partly because consultants make money incorporating them into models and imposing them on clients. I agree that a great deal of material should not be memorized and quizzes are useless (subjects like diversity for example are heavily attitudinal). However once an organization decides that all courses must be evaluated a certain way, especially a level 2, they want to do it the least painful way. That is the “courseocracy”.

Here’s my take on 70:20:10 http://whatyouneedtoknow.co.uk/702010-framework-breaking-things-right-way/

James and Marcella, thanks for bringing up the 70:20:10 model. For people who aren’t familiar with it, it says that “roughly” 70% of learning comes from doing “tough jobs,” 20% from other people, and 10% from formal learning. It’s often used to persuade L&D departments to look beyond shot-in-the-arm courses when trying to improve performance.

It’s not based on much research; instead it’s a shorthand way to summarize an idea. However, the numbers give the impression that this is a science-y formula, which can easily lead to misapplication by people who are looking for a quick solution.

I agree with the authors of this critique in ATD’s Science of Learning blog: “Learning professionals need to keep in mind that the 70:20:10 concept is a conceptual or theoretical model based on retrospective musings by executives about what made them successful and broad summary statements of the findings. It is neither a scientific fact nor a recipe for how best to develop people….The right training at the right time can have a significant impact, but whether that is 2 percent or 22 percent is impossible to say.”

Great points! And thanks for the 70-20-10 links. Sometimes companies can use 70-20-10 as an excuse for cutting how much training people get, so having solid resources to show that the numbers are mythical could come in very handy one day.

A couple of myths I like to debunk are Seth Godin’s “No more than six words on a slide – ever” (which he breaks on video here [link]) and the Mehrabian (or 7-38-55) myth [link] that only 7% of a spoken message is conveyed through words, with 55% through body language.

Your list at the end gave me food for thought, too. Especially “No one will learn from a normal web page with scrolling.”

Thanks as always for challenging conventional wisdom.

Sorry, the Seth Godin one is here [link], in a comment near the bottom.

For people who want to see how the 70:20:10 model is interpreted, this PDF is interesting. Pages 8-10 describe the many different ways the model is explained and applied.

I suspect the 70:20:10 numbers remain because they give the model a science-y appeal, even though they also draw criticism. It would probably be harder to propagate a model with a less statistical name, like “Don’t Forget Informal Learning” or “Many Ways of Learning.”

The informal learning is a myth on its own..

Many web 2.0 symposium organisers love it.!

Hi Ger,

Is it your assertion that people only learn under the tutelage of a sage instructor in a formal setting? That learning isn’t an internal biological process but rather one that is externally regulated?

If neither of these are true, I’m curious to see what your definition of informal learning entails as a myth. While I believe that informal learning doesn’t work exclusively (people = idiosyncratic), I do believe that there is a place and a space for exploration and growth beyond the formal learning space.

Dear Steve (see below),

If you – as new worker – have the privilege to work assistant with an expert on the job, I would not call that informal learning but private teacher (part of the 20%??). But you will alos learn traditional habits.

I once visited Uzbekistan and saw that they chalked the lower part of concrete.lampposts. I wondered why, until I saw that they do the same with trees (against termites or so?) I think that lamppost originally were made of trees?

A big danger of informal learning is that the good/wrong feedback often is missing, like i that other myth: wisdom of the crowd).

To eliminate the imprecise percentages, the U.S. Army developed the Full Spectrum Learning model, which in my opinion, does a much better job of showing how the various forms of learning can be applied in an organization – Full Spectrum Learning

The most common myth that affects my training pitches is:

“It’s too expensive. I can’t have my guys not working for [x hours, or y days] while they get training.”

…Followed closely by:

“We’ve tried training before, but it didn’t work and everyone hated it.”

Those myths are hard to break, because historically there are no metrics generated for how behaviors changed, or how much the ROI is for [x hours / y days] of training.

I need a myth buster for debunking previous failed attempts, and promoting ROI and behavior changes for future events.

– Rick

Rick, it sounds like you’re in a tough spot. It sounds like they’ve been designing training that doesn’t meet the needs of the users (“everyone hated it”) and that might be focused on the wrong problem or wrong solution (“it didn’t work”).

It might help to encourage stakeholders to get involved in diagnosing the problem more carefully, rather than letting them just hand over a lot of content for the next training project.

For example, if they have to identify how they’re going to measure the success of the training (set a business goal) and help you analyze why people aren’t doing what’s necessary to meet that goal, they’ll help create more on-target solutions and be more committed to the project’s success.

If this sounds feasible, there are some tips for the process in How to Kick Off a Project and Avoid an Information Dump.

Thanks Cathy! Love you straightforward approach.

Just love this!!! I retweeted it immediately!!!

Thank You for this blog. As an instructional technologists our discipline should have zero tolerance for myths, yet some practitioners seem to hang on to discredited theories like ticks on a hound.

Even worse, less scrupulous practitioners use myths as a way to gull clients and profit by untruth.

Here’s a good myth-busting book that I’m reading now: Make It Stick . It’s a very accessible summary of what research shows works to help us learn.

. It’s a very accessible summary of what research shows works to help us learn.

Myth – I had a client who insisted the word Incorrect could not be used when giving (constructive) feedback on a question as they thought it would demoralise the learner.

Hi Cathy,

Your post is really comforting. Having just completed an MA in Education (Adult), focussing on e-Design, my course was saturated with these kinds of myths. Learning styles is STILL actively a part of an assessment criteria a my place of work. In uni, people were constantly referring to learning styles as an integral part of lesson planning and design.

Worse still is the myth of the ‘self -directed learner’ whereby adult learners (and now children ) ‘know what they need to learn’. Another myth is that technology will improve learning- speed it up, and that the teacher is now effectively relegated to ‘guide on the side’. This issues are having huge ramifications for the whole notion of teachers as teachers, rather than support agents. (See Kalantzis & Cope for more of this kind of mythology).

Although training has a different focus than formal education – I think that the myth of ‘engagement’ whereby everything is ‘fun’ and ‘easy’ acts to prevent the very engagement is seeks to achieve, because people recognise that it is light and tend not to recruit the kind of cognitive approaches that are necessary to ensure learning (I.e attention sustained, trial and error, reflections, practice, revision- effortful thinking- see Daniel Kahneman 2011 for more in ‘Thinking, Slow & Fast’).

Finally, when these myths were discussed in my class, most of the cohort did not accept them as myths – despite the research ( see Kirschner & van Merrienboer for a great paper that covers most of what you are discussing).

So, YAY to you for keeping up the debunking!

Hi Cathy,

Great post! I just wanted to share this recent article on the learning styles myth by Jarrett:

http://www.wired.com/2015/01/need-know-learning-styles-myth-two-minutes/

and this link by Kirschner and Van Merrienboer about “Urban Legends in Education”: http://ocw.metu.edu.tr/pluginfile.php/3298/course/section/1174/Do%20Learners%20Really%20Know%20Best.pdf.

The myth that is realy frustrating to me is that my clients often times say: “Learners need access to resources in case they want to learn more” without asking the critical question: IF they want to learn more then WHY would that be? What exactly would the learner try to accomplish and what would they need to succeed?

The biggest myth: good lecturing = education *)

See the scheme on this page to make you think: http://iss.schoolwires.com/Page/508

*) Modern version: video recoderded lectures in MOOCs = even better education.

So you made up the numbers? Thanks for starting another ISD zombie. I’m sure I will start seeing those numbers soon. : ) We love the zombies because they let us escape the work needed to understand performance problems, and numbers make statements look real.

Thank you again for speaking what we all need to speak. If I ever hear the phrase “high-level overview” again, then it’s timeto retire

We perpetuate failure when we do not allow people to learn from failure. In the contemporary work environment, failure is constant. Everyone is asked to do what they know not how. Yet these very same folks are intelligent, resouceful, imaginative, etc. True human resuorces. Why do we curb such? Especially when the task MUST be done and then red Ituce timelines, resources, MONEY?

Too many suicides on my past projects for whatever reasons. Why can’t an honest person educate and train others in order to benefit all?

Another great blog Cathy.The persistence of some of these myths is extraordinary. Learning styles in particular seems to be almost as resistant to the evidence as the NRA.

We are used to politicians misusing statistics but remarkably naive about the myths in our own industry. I still see the classic “We remember 10% of what we read, 20% of what we hear etc. ” quoted regularly. Of course the underlying point behind that one, like the idea behind 70:20:10, is valid – we learn far more effectively through practice and experience. But since that is self-evidently true, why the need to dress it up in spurious statistics?

On which note, here is an earlier rant on dodgy stats

http://blog.unicorntraining.com/2014/06/07/the-average-on-line-learner-is-34-years-old/

I think you have to be careful of “myth busting” as you invariably perpetuate another. You’ve stated “you must narrate elearning” as a myth, yet the book you recommend at the end by Ruth Colvin Clark has a chapter dedicated to “Present words as audio narration rather than on-screen text” (Chapter 6, 3rd edition)

” It’s one of the most common excuses for inflicting slow narration on elearning users.”

The science is suggesting you should have narration, is it not?

Julian, thanks for your comment. Ruth Clark’s book points out that narration is useful *when the visual is complex* (such as a graphic that isn’t self-explanatory). Here’s a quote: “We recommend that you put words in spoken form rather than printed form whenever the graphic (animation, video, or series of static frames) is the focus of the words and both are presented simultaneously….we recommend that you avoid e-learning courses that contain crucial multimedia presentations where all words are in printed rather than spoken form.”

The author’s aren’t recommending that all elearning be narrated. They’re saying that when you present an important, complex image that’s the focus of the material, you explain the image in spoken words rather than text. She offered as an example an animation that shows how tables relate in a database. “The visuals are relatively complex,” the authors write, “therefore, using audio allows the learner to focus on the visual while listening to the explanation.”

This doesn’t mean “all elearning must be narrated,” which is the myth I regularly target. In most of the corporate elearning I see, the graphics are stock photos of smiling people or business settings, and the focus is the narration, not the “eye candy.” There’s no reason to “explain” the graphic in narration because the narration isn’t even talking about the graphic and the graphic is simple.

As another example, I’m creating a course on scenario design. When I want to explain how to create the plot of a branching scenario, I show the plot of a branching scenario (like a flowchart) and explain it in audio, because the graphic is complex. While I talk, I point at parts, zoom in, etc. At another point, when I present a summary list of tips for designers, it’s just text on the screen (and in a job aid). There’s no reason for me to read the list to the learners or to display, say, a stock photo of a person drawing a flowchart in the air while I read the list of tips.

For additional studies that were done on adult learners and show the effects of unnecessary narration, see Do We Really Need Narration?.

No I think they are recommending that you narrate where possible – the usual scientific caveat, that it isn’t always possible. If you read the whole chapter in context I think you come to the conclusion to narrate where you can. “When simultaneously presenting words and the graphics explained by the words, use spoken rather than printed text as a way of reducing the demands on visual processing” (p119). That’s quite clear to me.

Also John Medina recommends multi-sensory processing to better encode memory:

brainrules.net/sensory-integration/?scene=1

So it’s extreme and unecessarily provacative for you to say it is a “myth” – “not entirely accurate” is a better description if you must challenge it, but there’s evidence to suggest they are correct. I’d rather people heading to adding narration to everything rather than the dull text based page turners which dominate elearning development.

the core of the discussion in teh book. of Clarke and Meyer is the limited capacity of the working memory. ( wrong chosen name, suggesting that the rest of the brain is not active) and the idea of spreading the information over two channels, audio and visual.

1. when you put the same info in text and narration you spoil the already limited capacity.

2. when you add backgroupd music you spoil audio capacity

3. when you add nice pictures you spoil visual capacity.

yes i know, then people play the motivation card. The most famous example is from the multimedia book from Meyer. Children learn better to read when you do NOT add pictures to the text. (1935, but we still you these poster with A= Apple etc..)

Very insightful article. Your last two points about designing effective training are very popular and definitely important to consider when creating an elearning training program.

The LearningZen course viewer is a training program that will be available within the next couple months. If you’re looking for an example of effective elearning or a training program to provide for a company, check it out here: http://blog.learningzen.com/2014/12/sneak-preview.html

Thank you — food for thought, both from the article and the comments.

I am a student of Instructional Design at Walden University and this week we discussed learning theories. Regarding the Right Brain/Left Brain myth, although the two sides of the brain tend to specialize in specific areas, “people rarely, if ever, thi exclusively in one hemisphere; there is no such thing as left-brain or right-brain thinking” (Ormrod, Schunk & Gredler. 2009. Pg 35). The authors go on to explain that the two sides of the brain are joined by the corpus callosum which allows the two sides to be in constant contact with one another. Might be a good myth buster to use for clients who are health care oriented! Thanks for the fortuitous blog – it helped connect my class work to the real world.

Forget to mention the name of the text we are using in our class: Learning Theories and Instruction by J.E. Ormrod, D.H. Schunk and M. Gredler.

This post is so timely, just about month ago a co-worker told me learning styles do in fact exist because “that’s why things are presently differently to kids in school.”

Very interesting post Cathy and some very interesting comments, so thanks to everyone.

My comment is about organisational culture and its effect on the activities learners undertake after they have completed some e-learning and perhaps attended a workshop.

I design and run Sales Coaching Workshops for large clients. My biggest concern is always “How will these guys be able to coach their sales people once they get back to the job?” I can show them “how to” activities, I can eliminate quizzes, I can follow all of the great advice on Cathy’s blogs but how can you get an organisation to shift?

A typical client will say “We want our people to coach 50% of the time” I ask “How much coaching do they currently get from their boss?” The response is always “Oh, don’t expect our senior managers to coach, can’t you just get our first line managers to coach more through your training?”

I guess Cathy would say I need to solve that problem at the outset when I am developing the learning but I have yet to find an organisation that has a senior management team that follows best practice on any subject, not just coaching. I read a simple saying recently that stuck with me “Avalanches roll downhill”. How can we get our learners to “improve their work habits” if they do not see their boss doing the same?

Does anybody have any thoughts on this?

I don’t have any solutions, Fred, only commiseration. I run into this frequently as well. How do you get the top level leadership to coach and model the behaviors (often leadership behaviors) you want the low man on the totem pole to exhibit? A training session is like planting a seed. In order for the seed to grow and flourish, it needs to be nurtured continuously, not just planted.

Thanks Eowyn. You are correct, I guess we are planting seeds and hoping some will grow and flourish.

I was on a 2 hour call yesterday with a global client – talking about their 20, yes 20, KPIs on sales performance and how they wanted their sales managers to coach to improve the 20 KPIs.

I will be running a 2 day learning workshop in March to help to teach them how to coach. Ongoing learning inside the organisation and cultural shifts are what is needed however it is difficult for a trainer to influence and enable that long term, organic organisational change

Hi

I’m biting my lip.

Here’s an extract from a blog I wrote a while back:

Harry Chapin’s ‘Flowers are red’ http://youtu.be/1y5t-dAa6UA was inspired by a report card his secretary’s son got which said, ‘Your son marches to the beat of a different drummer, but don’t worry we’ll have him joining the parade by the end of the term’.

Blog here: http://whatyouneedtoknow.co.uk/flowers-red/

From what everyone seems to be saying here about learning styles, there are no different learning styles, therefore everyone learns in the same way, and we just need to get people marching to the drum of all the ‘right-minded’ people.

Maybe instead of saying what the myths are, what about the truths/facts.

Andy, thanks for your comment. I referred to the facts in my post and in the material linked from the post. For more facts summarized in one book, see Make It Stick , a book that compiles a lot of research about learning.

, a book that compiles a lot of research about learning.

One of many statements from that research-based book: “While it’s true that most all of us have a decided preference for how we like to learn new material, the premise behind learning styles is that we learn better when the mode of presentation matches the particular style in which an individual is best able to learn. That is the critical claim.”

Research fails to support that claim. Instead, according to the researchers cited in the book, “When instructional style matches the nature of the CONTENT, all learners learn better, regardless of their differing preferences for how the material is taught.”

If you’ll look at the post Learning styles: Worth our time? linked above, you’ll see meta-analyses that come to the same conclusion. They suggest that rather than spend time adapting content to learning styles, learning designers should use that time to apply other techniques that have been shown to work, and which are described in the post.

It’s not about squashing personalities. It’s about helping people learn as effectively as possible, without wasting our time and energy or theirs. We show the most respect for learners when we use the most effective techniques to help them reach their goals.

I don’t think anyone is saying that everyone learns the same, only that the boxes of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic that we have been dumping learners into do not have sufficient evidence backing them up. If anything, losing those labels and boxes opens up learning as much more personal and individualistic.

Hi Marcealla/Cathy

If not everyone learns the same, then some people will learn differently. Can you have it both ways/

VAK is only one way of looking at learning styles – it’s not the only way. In fact, the work I did in the 80s was about helping students to explore themselves as learners and find out what was effective for them as, I’m afraid teachers/trainers/L&D practitioners all have their views on what’s effective (myths) – and they will all vary.

I’m afraid I don’t agree with the ‘critical claim’. I’m sure some people have made that claim but it was never the starting pointing for us. As teachers it was much more about engaging students, especially at the beginning of a course or topic as “most all of us have a decided preference for how we like to learn new material”. I think if you accept that sentence you have to accept that there is something in learning styles, it maybe incomplete, it may have been distorted by some/most, but I think it is mistake to totally discard it.

Sorry Cathy: I couldn’t see any facts/truth in the post – I saw the ‘myths’ which I would suggest are not always myths e.g. ‘Training is a one-time event or course’ – well I took one course in driving and never took another.’Our job is to make this information easy to understand and remember’ I certainly think that’s a part of teaching/training – I’m afraid when people hide information as if it’s clever to do so, it just annoys me as a learner + I think Lynda.com is doing a pretty good job and CommonCraft and doing great at making difficult things easy to understand… I could go on.

Earl Stevick wrote a book about 7 successful language learners and looked at what they did differently and the same – http://www-01.sil.org/lingualinks/languagelearning/booksbackinprint/successwithforeignlanguages/success.pdf

In the summary he writes:

‘But a learner should also be cautious about accepting guidance from us specialists in language pedagogy. Too often, we fail to resist the human urge to ‘construct an entire method on one brilliant insight’ – to ‘latch onto one key idea and follow it long and far,’ as Karl Diller once put it.2 Somebody notices that much can be gained, at least with certain learners, by practicing sentences aloud before seeing them, or by picking up grammar without formally studying it, or by understanding grammar before practicing it, or by maintaining a tranquil atmosphere in class, or in some other way. These insights all too easily lead to the conclusion that reading should be minimized, or that grammar study should be done away with, or that it should be given first place, or that teacher-generated challenges are always bad or

the like.’

I think most things in life fall on a continuum between science and art. It wasn’t that long ago that scientists were telling us that we learnt through stimulus and response.

Andy, what I’m arguing against are global rules thoughtlessly applied. For example, “Training is a one-time event” is a global rule that in the corporate world, which is the subject of this blog, is applied to almost every learning “intervention.” For example, many think we can give people a 4-hour shot in the arm and fix longstanding performance issues. This often doesn’t work.

I’m saying we should QUESTION this assumption rather than casually accepting it as a fact. This in fact agrees with the quote you posted about the dangers of “constructing an entire method in one brilliant insight.”

And again, for the last time in this discussion, no one is saying people don’t have learning preferences. The research linked in the post above, in the comments here, in the comments to that other post, and in many more studies cited in many more L&D blogs and available through a search in Google Scholar says that there are *more effective* ways to teach than by, for example, “adding visuals for the visual learners,” which is how learning styles are used in corporate training.

I followed the link to ‘Make it stick’ in this blog. It contents very interesting myth-busters: especially the wisdom that for teachers and students a cramming course feels more efficient and effective then a spaced courses, while the research evidence shows the opposite.

Cathy,

Great Post! And a great discussion!

For those WHO WANT TO BE A PART OF THE SOLUTION, join The Debunker Club.

http://www.debunker.club

Please spread the word!

= Will

Myths about training and learning cause so much waste that they became a target of the OECD’s CERI project, set up in 1999, which published a great article on “Neuromyths” http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/neuromyths.htm

Sanne Dekker and a team from Amsterdam and Bristol used the Neuromyths article as the foundation for a study into the prevalence of learning myths with teachers (Neuromyths in Education: Prevalence and Predictors of Misconceptions among Teachers http://dx.doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpsyg.2012.00429). This showed how widely believed myths were and how often it was those who considered themselves most informed that believed the largest number of myths.

I ran a similar experiment, which wasn’t very scientific, with a group of medical educators in Australia and found very similar results. The group included a few people with psychology degrees and MEd’s, who performed very similarly to the rest of the group.

It’s great to see more people trying to be myth busters. It has been a long road trying to dispel axioms that are easy to remember but wrong.

The moral of the story: question what you’re told. Find evidence. Use the research. If L&D wants to be believable and influential as an industry, then we need to be credible and reliable.

David, thanks for your comment. In my own experience, I’ve seen the same paradox: often, people with advanced degrees believe damaging myths. Unfortunately, the source of those beliefs can be their own degrees.

I sometimes get questions from graduate students who are completing assignments for a degree in instructional design. When I look at the syllabus for their course or read their assignments, I see that they’re being told, for example, that their instructional design should take into account the “four learning styles.”

Some students are investing painful amounts of money to hear that myths are true and, often, to learn nothing about what a business needs and how their role should help meet that need.

Thanks for sharing your insight Cathy. As a designer for e-learning, we should understand how certain myths can interfere with our ability to effectively present course material. In order to design presentations that will allow your clientele to retain the information shared, we must first understand that as designers we have an important role in helping them to retrieve and retain the material. For instance, if we enter the lesson already believing our clientele needs to have the information presented in a slide show format instead of a webpage with scrolling, we are limiting the possibilities that we have to share the information.

Hi Cathy,

I currently work as the Coordinator of Instructional Technology at a small liberal arts college, and a big part of my role here is to help train faculty with online and hybrid learning. I can’t believe how many learning myths exists, specifically for the online learning format. Myths such as ‘online learning is only for the highly motivated student’, or ‘online learning is an isolated activity with little social interaction’. Myths about the traditional classroom are slowly starting to fade, but those concerning online learning are still going strong. It’s keeping many students and instructors away from the world of online and e-learning, and that’s a shame. We in the ID community really need to speak up, a thing you do great with your blog!

So let me get this straight? Pegasus the flying horse doesn’t really exist?!!!

Again great article. Thanks Cathy.. Quite interesting article and comments… Thanks to everyone!!!