Here's a summary of action mapping. This was originally the handout for my keynote at the 2014 Online Learning Conference by Training magazine.

My point

We face a cultural challenge: many people -- clients, employers, colleagues -- see us as information designers. As a result, we obediently design presentations with quizzes, creating content that often has nothing to do with the urgent needs of the organization.

Instead, we should see ourselves as analyzing problems and, when appropriate, designing experiences that solve those problems. The experiences are realistic activities through which people make decisions and learn from the results of those decisions.

Our projects should be tightly focused on improving a performance measure that the organization cares about. That measure could be anything from increased sales to fewer calls to the help desk, but it won't be "make sure all employees complete the training." No one but L&D cares about that.

Action mapping is my visual approach to instructional design. It can help you get clients and SMEs to agree to these activity-rich, relevant materials. It's a streamlined mashup of performance consulting and backward design.

Do this with your client and SME

Do at least the first two steps of action mapping with your client and subject matter expert(s). Often, one two-hour meeting can cover the first two steps of action mapping. For more, see How to kick off a project and avoid an information dump.

Our larger goal is to win the participation and respect of our clients. For more, see Three simple but powerful ways to get love from your leaders.

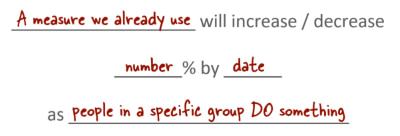

1. What's the problem? How will we know we've solved it?

Ask, "What are we currently measuring that tells us we have a problem?" and use it to create a project goal. For more, see How to create a training goal in 2 quick steps.

2. What do people need to DO, and why aren't they doing it?

With your SME and maybe your client, too, list the on-the-job behaviors that people need to perform to reach your project goal. List visible, specific behaviors, actions that a guy with a clipboard could observe and check off.

You're writing performance objectives, avoiding words like "define" or "identify" or other verbs that take place only on a test. For more, see Why you want to focus on actions, not learning objectives.

Have your SME prioritize these behaviors, and then with your SME take the most important ones through this flowchart, one at a time. You're confirming that training will actually solve the problem, and you're looking for easy, non-training solutions.

Don't skip the flowchart. If you assume that every action requires training, I guarantee you'll waste time designing stuff you don't need. That's time you could have invested instead in creating challenging, satisfying activities.

3. How can we help them PRACTICE what they need to do?

For the behaviors that really do need training, brainstorm activities that will help people practice making the decisions that they make on the job. You might brainstorm these on your own and then run them by your SME.

These activities are contextual. They have two important features:

- A character (often "you") faces a specific, realistic challenge.

- The feedback shows the consequences of the learner's choice.

The following activity is contextual (though barely; it's really basic).

The feedback lets people use their brains to draw conclusions.

There are a lot of posts on this blog on writing activities. Here's one to get you started: Makeover: How to write challenging scenario questions. For feedback, check out Feedback in scenarios: Let them think!

4. What information MUST they have to complete the practice activity?

Finally, identify the information that people absolutely must have for each activity. Also decide whether the info needs to be memorized or can be looked up in a job aid.

You end up with a map that identifies the activities you'll use and excludes unnecessary information.

Create a stream of activities

Resist the temptation to present and then quiz.

For example, the following activity could come first in a course, with no information before it. Instead, the information is included in the activity.

For more, see Why you want to put the activity first. For research supporting this approach, see Throw them in the deep end!

Conclusion

Our goal is to hear this less: "Could you turn this information into a course?" and hear this more: "We have a performance problem. Can you help?"

We aren't information designers. We analyze performance problems and design learning experiences, helping our organizations meet their most important goals.

For a lot more, see my 2013 L&D manifesto, the decidedly non-serious design manifesto.