By Cathy Moore

Let’s say we’re designing a course that will help widget sales people overcome buyers’ objections. The objection we’re focusing on right now is this one: “I’ve read that your widget creates a lot of heat.” We have a specific way we’d like our sales people to respond to that objection.

Some people in our audience are familiar with the concerns about heat, while new people might not know as much.

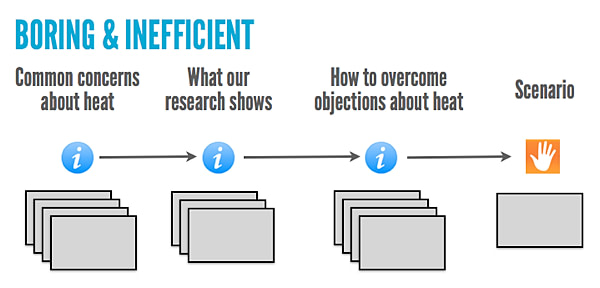

How do you think most training designers would approach this? I think they’d do it like this.

The designers would think, “First, we’ll tell them the common concerns about heat, to make sure everyone knows them. Then we’ll tell them what our own research shows about the heat and why it’s not a big deal. Then we’ll tell them how to respond to heat objections, and finally we’ll let them practice with a scenario.”

Why did I label this “boring and inefficient?”

- The learners have to trudge through many screens before they finally get to use their brains.

- Some people already know the stuff presented on the many screens.

- The how-to info is presented immediately before the scenario, making the scenario a simple check of short-term memory.

Here’s a more efficient approach that has the added advantage of helping people learn by doing.

We immediately plunge learners into a realistic scenario — followed by another and another. Then we concisely recap what they’ve figured out through the scenarios.

The material feels like a stream of activities, not pages of information followed by one lonely memory check. The recap will be memorable and concise because it refers back to concrete examples, such as, “As you saw with Ravi’s objection, it’s best to …”

But what about the information?

We can include the information about heat issues as optional links in the scenario.

Now our material is more efficient and a heck of a lot more interesting. People who already know all about the heat issues (or, importantly, think they know) will forge ahead without reading the optional documents. Newer or more careful people will check the documents to make sure they know what’s going on. Both groups will figure out if they chose correctly when they see the results of their choices.

In addition, the optional documents are low-tech PDFs or pages on the intranet, the same documents that people use on the job. This makes the information much easier to update and puts the scenario in a more realistic context.

But they might just guess and miss important information!

The usual argument for the boring and inefficient approach is, “We have to make sure everyone is exposed to the information.” But who cares whether they’ve been exposed to it? What we care about is whether they know it and can apply it.

So we’ll design scenarios that make them prove they know it, and we’ll design enough challenging scenarios about the same important information to make sure no one is slipping through the cracks. And if we’re really worried about information being missed, we can include it in the feedback, as shown in this post.

For some research support for this approach, see Throw them in the deep end.

But you didn’t show them how to overcome objections!

We haven’t led them by the nose through the Heat Objection Handling Process because we want them to figure it out through experience. Our feedback will help. For example, if someone chooses option C above, they’ll see the following result:

“I’m not surprised that your studies don’t show any problems,” Ravi says, sounding a little annoyed. “But Widget World does rigorous, independent testing, and they found heat issues. What can you tell me about the heat?”

From this, learners realize that shoving research at the customer backfires. It sounds like option A was the better option, and for their next step, they’ll want to calmly discuss the concerns. (This post goes into more detail on why we’re just showing the result rather than telling the learner what they did right or wrong.)

More design time, less development

This approach usually requires more in-depth discussions with the subject matter experts and more careful script writing. However, it often results in quicker and easier development. We’re building fewer screens and, happily, we feel less compelled to add bling in a desperate attempt to make a boring presentation more interesting.

Scenario design toolkit now available

Design challenging scenarios your learners love

- Get the insight you need from the subject matter expert

- Create mini-scenarios and branching scenarios for any format (live or elearning)

It's not just another course!

- Self-paced toolkit, no scheduling hassles

- Interactive decision tools you'll use on your job

- Far more in depth than a live course -- let's really geek out on scenarios!

- Use it to make decisions for any project, with lifetime access

I totally agree! We call this “creating ‘ah-ha’ moments”. When well structured activities precede any formal instruction, they create opportunities for learners to figure out solutions themselves. That way we shift our roles from trainers to facilitators of learning.

Marion, thanks for your comment. The “facilitator” role is also a good one for motivation, because it says to learners, “I know you’re an adult, so instead of spoon-feeding you bland, pureed basics, I’m going to give you this much more interesting steak to chew on.” Or something like that.

I love this approach and can’t count the times I’ve failed to convince clients that we should use it. The argument – which may actually hold a drip of water – is that the complexity of some content (like the internal operation of machinery) requires a full instructional treatment and should be taught whollus bollus so that the student understands how everything connects and effects each other. They argue that having this information as reference or even creating an embedded mini-lesson would encourage the student to find the isolated bits of information to answer the question but miss the big picture.

The closest I’ve come is to teach the bare basics of teaching points a, b and c and then have the scenario both provide opportunities for application in context and feedback that augments (so a2, b2, c2). Subsequent scenarios then challenge the learner to apply that augmented information. This has worked well in troubleshooting scenarios where the learner is assumed to already understand fundamentals but can then learn the finer points through application and feedback (from either the systems response or input from their virtual supervisor).

I’m still looking for the client who is brave enough to ditch the initial mini-lessons.

Hi Ian, I think your compromise is a good one, using scenarios to introduce and apply the finer points. I agree that sometimes it’s best to teach at least some stuff first if the material is complex, such as the internal workings of a machine. Unfortunately, a lot of what we’re supposed to “teach” is pretty close to common sense, as we’ve all seen in compliance courses, for example. I hope you find a brave client!

Thank you Cathy for this article. As I am looking to jump start my career into learning and development, I am glad to see your refreshing perspective.

I believe that this method of practice > info > practice, provides participants not only an opportunity to apply the knowledge they received, but also a chance to measure their improvement with the ‘before’ and ‘after’.

Perla, that’s a good point. When we perform less than great on an activity, we go into learning mode, and if we can see our performance improve quickly in the subsequent activity, we’re immediately rewarded, and it’s a much more satisfying award than messages like “Correct!”

Hey Cathy — here’s an interesting little bit of research on the idea of test-then-tell (ironically, it’s from a blog post by Jonah Lehrer, who presumably knows a lot about learning from mistakes): http://scienceblogs.com/cortex/2009/10/22/learning-from-mistakes/

Julie, thanks for that link. The money quote for me: “Kids learn material much faster when they screw up first.”

Thanks, Cathy. As you mentioned, this type of approach requires much more contact with the SME, but results in more meaningful training. (I assume you write into your contracts that amount of time you’ll need the SME for scenario development?) I also like how this process stresses the importance of relevant content rather than presenting the content in a visually-interesting way. We elearning developers are a little too impressed with our visual chops. –Daniel

Daniel, I agree it’s important that the client understand from the start that you’ll be needing more SME time than they might have been used to providing. If you use action mapping, I usually advocate for including the SME from the very beginning, when the business goal is established. When I did design for clients, I had a clause that didn’t specify exactly how much SME time I needed, but it did specify that the SME had to respond within X days or I wouldn’t be able to guarantee delivery of the script by the deadline.

I see a connection …

Classes should do hands-on exercises before reading and video, Stanford researchers say

http://news.stanford.edu/news/2013/july/flipped-learning-model-071613.html

Thanks for the link. For people who haven’t read the article, here’s the gist: “Findings revealed a 25-percent increase in performance when open-ended exploration came before text study rather than after it,” and they got the same results for video presentation of the information — activity, then video worked better. Their audience was grad students who had no previous knowledge of the material.

I think the important proviso is that the hands-on was with an interactive model that supported exploration and allowed the students to easily infer cause/effect relationships.

The trick is in ensuring the activity media is appropriately sized to the learner.

Example: a full-motion flight simulator will provide very realistic hands-on practice/feedback, but naive exploration will not lead to any learning (just crashing). However, a simple interactive model that demonstrates how stick, rudder, throttle affect the aircraft can provide a great opportunity for a novice to grok the principles of flight before getting into the nitty gritties. So I think it is all about right-sizing that activity to the learner/phase of learning.

Ian, that’s a great point about simplifying complex situations so newbie explorers can figure out the basics. It can be really useful to start with basic scenarios and move into more complex ones as people show that they’ve got the basics.

“Have you had any success putting the activities first?”

Why, yes I have. I will confess it was a very last-minute thing.

I was scheduled to give a 90-minute session on how to build job aids. The evening before, I decided there was too much explanation and background (translation: me, talking) before the mini-exercises. I reworked one exercise to say “describe a work task you know; decide if it makes sense to build a job aid for the task; discuss with your neighbor.” I created a handout about making the job-aid decision, the equivalent of your PDFs (as well as an example of a job aid to guide decisions).

What happened?

– People started with a task they chose (= their own work context).

– People used the reference when it made sense to them to examine familiar task in a new light (= application).

– People had the chance to talk not only about their own decision but someone else’s as well. (= further examples, reflection)

This may have been the single smartest thing I did that month.

Dave, thanks for the great example! Your points about context, learner control, and discussion are important.

I’ve done the same thing, except I did it *after* inflicting myself on an audience. I heard myself preaching about starting with an activity and realized as the words left my mouth that I had failed to do that myself. The next iteration of the workshop started with the activity. 🙂

Hi Cathy,

You mention low-tech pdfs. what is a low-tech pdf? I guess I dont know what a high-tech pdf is either.. : ) Also, is the only purpose of putting the “extra information” in low tech pdf or intranet page the fact that the learner references these two areas in his daily job? In other words, if the learner does not often use his intranet for this purpose, then putting the extra information there would not be something you would recommend I assume…

Thanks in advance!

Ryan

Ryan, I call a PDF “low tech” because compared to the Flash interactions that most readers create, it’s quick and simple to make and easy to update. For the optional information, I recommend using whatever format is currently being used on the job. If there are no job aids being used and you want to create one, I’d recommend working with the SME and some people currently doing the job to figure out which would be the most useful format.

Allowing the learner to use their prior knowledge and frames of reference to make a decision encourages them to really engage with the material and makes for a more meaningful learning moment. I love presenters who employ this tactic. Also to Ian’s point (21 August 2013 at 6:06 pm) about ‘right sizing’ the activity to the learner, I’ve been on the recieving end of many trainings (some as inspired as yours Cathy but mostly not. lol!) and I appreciate when the material is not so basic as to immediately make me think ‘I already know this stuff’. If a presenter leads with something kind of challenging–not Mensa material or anything–but something that will ignite my curiosity (and maybe give me the opportunity to learn from a mistake) then this is more impactful for me.

I have designed a whole teacher education curriculum that is activity based. However, it doesn’t heavily depend on scenarios. Choosing to use scenarios depends mainly on the context or situation. I have found most interpersonal communication type situations to work best with scenarios. For everything else, scenarios sometimes fall short and other means of activity are required. We began with using scenarios but quickly realized that activities, i.e. the learn by doing approach (which I totally agree is high on the design end and lower on the development end) can be applied to project type of activities. Projects could range from research projects, DIY type of projects, and opinion based activities which ask the learner – What do you think about this content?

Kunali, thanks for your comment. I agree that the opening activity could be any hands-on activity. I used scenarios in my discussion because most of my readers are designing stand-alone, asynchronous elearning, where it’s hard to provide feedback on research or DIY projects.

Dear Ms. Moore,

Thank you for sharing information regarding the importance of incorporating a hands-on component in the learning process. My learning style is largely self-regulated and kinesthetic, such that audiovisual presentation of material in a traditional classroom setting is insufficient. I have recently had the opportunity to explore the two-store model, which proposes that we intake information via numerous sensory pathways, but are able to process only so much of that material at any given moment (Omrod, Schunk, & Gredler, 2009). As a working adult taking courses and raising a young family, I realize the role of an instructional designer to present information in a clear, succinct manner and recognize some of the limitations of information processing by the brain. Your discussion of the recap spoke to me as this is how I envision effective learning: A series of informational blocks (scenarios) that are summarized and connected in a specific, realistic way to encourage long-term recall. I appreciate your insights.

Best,

Sriya

References

Omrod, J., Schunk, D., & Gredler, M. (2009). Learning and the brain. Learning theories and instruction [Custom edition] (pp. 27-46). New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

I have been on the receiving end of training material that was information first, then activity. As a hands-on learner, I felt like I was suffering through the information until I could get to apply it. There were times where the application (i.e. activity) never came and I felt like the course had completely wasted my time. Or, I was “ordered” to go to a course where I already knew the information and an activity-first approach would have shown the instructor where the students were in terms of knowledge. Then, the instructor could have taken a break and determined if the content or level of the content could be tweaked to fit the audience. I realize that most courses cannot have their content altered significantly “on-the-fly” but perhaps, if the course were pre-designed to have different depths to the content, a more advanced class could go more “in-depth.” The differing abilities of the audience need to be considered when designing training (American Psychological Association,2013). The fact that people learn at different rates seems like a basic thing, but it often not considered in any type of curriculum or course.

American Psychological Association. (2013). Research in Brain Function and Learning. Retrieved from American Psychological Association: http://www.apa.org/education/k12/brain-function.aspx#

Diane, thanks for your comment. I agree that face-to-face training can (and should) be easily adjusted depending on the needs and pacing required of the audience. When I do live training, I base it on an informal HTML menu with many links to small collections of slides or examples, and the participants decide as a group which content we’re going to focus on. I could see this being extended to larger groups of trainers by highlighting the core elements on the menu that should probably be standardized in all courses, and letting the rest of the content (most of it) be decided by participants.

Many of my readers are designing standalone elearning rather than live, synchronous training, which makes it even trickier for them to accommodate different levels of experience or different pacing. That’s why I vote for putting helpful information as optional links in the activity.

Many of the eLearning modules I create are part of the core curriculum for everyone in our business unit which is around 3000 employees. After designing and developing several eLearning modules that would fall into the “boring and inefficient” category I tried a new approach. Based on feedback from learners, I have designed a few courses that began with “new” information (e.g., changes in the law that occured over the past year) followed by an option to “test out” of the remedial portion of the module and go directly to the quiz. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive particularly with more experienced employees. After reading your post, I’m thinking that scenarios would be an even better option than a quiz because it would require leaners to have to apply what they know to real-life situations. Do you think this approach is appropriate when you have learners coming with different levels of experience or are you setting up some to fail right off the bat?

Let’s not forget that up-front activities can also demonstrate to the learner what they don’t know, making them pay closer attention to the core training.

Ms. Moore,

Thank you for sharing this information. I am an elementary school teacher and an Instructional Design student. For me this post creates a connection between methods I use to teach math and how to approach situations I may face as an Instructional Designer. When teaching math I use the CRA method (concrete, representational, abstract). After presenting the lesson’s learning objective, I provide students with hands on manipulatives and a task that will lead them to discovering an important aspect of the concept being taught. This is the Concrete portion of the lesson. Once they have that understanding they relate to it by Representing it with drawings, charts or tables. They are then better equipped to solve the problem in its abstract form with actual numbers and algorithms.

I am just beginning this masters program and I have much more to learn but this post shows me that with some adjustments, learning theories can be applied in different situations regardless of age, subject or concept. Again, thank you!

Michelle