By Cathy Moore

Here’s a short scenario that uses a particular type of structure. What do you think about it?

Photo by naosuke ii cc

Spoiler alert! Play the scenario above before you read on.

What type of branching is this?

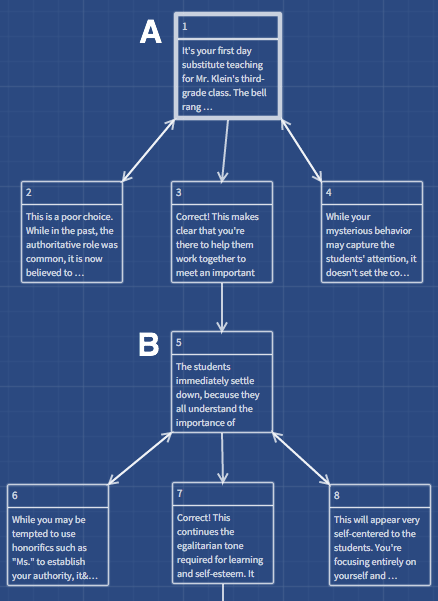

Here’s how the scenario looks as a flowchart in Twine. No matter what we decide at decision point A, we all end up at decision point B. It’s like we have no free will!

If you’re feeling cranky, you could call this the “control freak” approach to scenario design: No one may advance without first making the correct choice, and then all people must advance as one obedient mass to the same scene.

If you’re feeling more generous, you might call it a “teaching” scenario.

It might be helpful for raw beginners

The extreme control exercised by the designer could actually be useful in the following conditions:

- The people playing the scenario are beginners in the subject matter AND

- We haven’t preceded the scenario with a bunch of information telling people everything they might need to know.

In other words, people new to the topic learn about it through a guided experience first, not through an information presentation followed by a “practice” activity.

What could happen if we put the information first?

Let’s run an imaginary experiment. Let’s not start with the scenario. Instead, we’ll give our learners lots of do’s and don’ts about classroom management. We’ll follow that with a video of an expert talking about how honorifics like “Ms” supposedly squash students’ self-esteem, and then, finally, we’ll send them into the scenario to “practice what they’ve learned.”

Now that our learners are no longer absolute beginners, the relentless feedback and forced re-tries are likely to feel annoying and even patronizing.

“But we have to give them information!”

I agree, we do — after the scenario.

We can give people a chance to learn through the (very!) structured experience first, and then help them synthesize what they learned by giving them some reinforcing information. We can trot out the video expert after the scenario, for example, to reinforce the scenario’s message about honorifics.

Putting the scenario first does several things. It:

- Helps people gauge their pre-existing knowledge, if any

- Shows the learner through their mistakes that they need to learn this stuff, making them pay more attention to the information that follows

- Gives them a concrete, memorable story with which to organize the more abstract information that follows, possibly helping with retention and transfer

- Gives them beginner-level information in an engaging way, possibly motivating them to continue

For more on this activity-first approach, see my post “Throw them in the deep end!”

However, I still recommend true branching for most audiences

I focus on instructional design for adults in the working world. Most people in this world already have at least some previous experience or knowledge of the common topics covered in corporate training (how to treat people nicely, how to sell stuff, how to avoid breaking laws…).

As a result, I suspect that in most situations, a truly branching scenario would be more satisfying for the players. By letting people make mistakes, see the consequences of those mistakes, and draw conclusions, we’re saying, “I acknowledge that you’re an adult with a brain and life experience, and I trust you to be able to learn from more experience.”

Our careful handling of the branches, feedback at the ends of the paths, and optional help or resources along the way will help make sure that players are drawing the right conclusions without getting too frustrated. It’s all about choosing the appropriate amount of scaffolding for our audience.

For an example of a “real” branching scenario for people with some prior knowledge, try playing this scenario, which helps you practice managing a client who wants you to create a course when that might not be the best solution.

Scenario design toolkit now available

Design challenging scenarios your learners love

- Get the insight you need from the subject matter expert

- Create mini-scenarios and branching scenarios for any format (live or elearning)

It's not just another course!

- Self-paced toolkit, no scheduling hassles

- Interactive decision tools you'll use on your job

- Far more in depth than a live course -- let's really geek out on scenarios!

- Use it to make decisions for any project, with lifetime access

In case someone somewhere thinks that the classroom management scenario is serious: No, it’s not. It’s a spoof.

Thanks for clarifying. 🙂 Having spent some time in the classroom, I actually think you would get some mileage out of the three-legged elephant, especially if she had a unicorn horn!

I agree with you, Cathy, that more robust scenarios are better than the type shown here. However, I think that you can have good success with this type as well if they are built well. I would change the way this one was built to give real outcomes of choices, then give the learner a chance to go back and correct themselves. For example, if the learner chooses to tell the kids to sit down and shut up, rather than say, ‘That type of thing used to be okay, but isn’t anymore. Try Again.” say something like, “The kids ignore you and continue doing what they are doing. They were unaffected by your approach. Perhaps you should try something else to get their attention.” Then let them go back and make another selection. Additionally, rather than giving the learner confirming feedback and making them click Continue when they get it right, just continue the story. With those couple of changes, I think this simpler type of scenario can produce a decently effective outcome in less time.

Thanks for your comment. Your suggestion to first show the consequence (“The kids ignore you”) and *then* provide guidance (“Perhaps you should try something else”) is a compromise that I often end up suggesting to stakeholders who want to maintain some control.

My preference would be to remove the instructive feedback entirely, let people make mistakes and simply see the kids ignoring them, and provide optional help and *optional* “go back” links. That way, players can continue down a bad path if they want to, to see what happens. This can be far more instructive than seeing only the “right” consequences.

While the scenario teaches a rather extreme approach to classroom “management,” it’s simple enough that we don’t need so much interrupting feedback. We could just write realistic consequences that make pretty obvious what players did wrong and let them decide whether to go back and fix it or to continue to see what happens. My argument isn’t with the simplicity of the scenario but with the constant interrupting and forcing people to go back to do it “right.”

I certainly advocate for the approach you are recommending whenever possible. I agree that allowing people to take the wrong path out of ignorance or out of curiosity is a powerful way to learn.

I really loved this post, especially the vivid flowchart in Branchtrack. I’m in the process of designing IT Customer Service training for my university and I can see this going a long way.

Most of our customer service is handled by college students. That poses a challenge: they have little professional job experience, but they are often the go-to people for the other students we serve. So this means they’re starting to get the adult experience that we expect trainees to have, but there is a lot of opportunity for refinement.

I created a scenario based around your design here. What do you think? http://camerongoble.blogspot.com/2014/08/designing-scenarios-to-train-it-student.html

Cameron, thanks for sharing your BranchTrack scenario. I think it’s a good example of how immediate feedback can help the newbie learn in a more engaging way than a list of do’s & don’ts. I also like your idea of following the intro scenario with a more complex branching one that I’m assuming saves feedback for the end. Thanks!

Exactly right. By the finishing scenario, constant feedback would be inappropriate; saving all feedback for the end would encourage more holistic understandings of the entire process. We want our trainees to be cognizant in that way as a goal of the training.

Thanks for taking a look at it!

I really like the idea of presenting the scenario first. I am starting a project on financial planning. It is a topic people often claim to know more than they do. Allowing people to “crash and burn” in a scenario seems a safe way to allow people to see the cost of their mistakes and create a willingness to admit they don’t know enough about the topic.

I think it is important to have a place where the scenario is recapped and the concepts and teaching points are made explicit. Chances are many learners will have figured out the concepts with their mistakes, but it is important to help the learner make their connection explicit.

Yes, I think the relevant comparison isn’t between this type of scenario and a ‘deep’ one but between this and ‘at the end of this course… it is essential that you ….we all have to …’ Cameron’s example is good, it draws you in before you’ve time to put up resistance. I agree the learning points have to be brought out at the end, and that’s something I’ve not done well enough in the past and have taken on board.

Great article, but I definitely thought the ‘correct’ first choice was going to be ‘shout at them to sit down and shut up!’

I’m seeing a common thread in many of your posts, Cathy. Your post from September 2010, Learning Styles: Worth Our Time? informed us of the importance of instructing students in the strategies of metacognition. A post from September 2013, Throw Them In The Deep End, informed us of the significantly greater level of effective application students have when not explicitly taught every little thing. Similarly, this current post encourages greater student control and therefore expects greater fluency in the learning outcome. As an elementary educator, I am seeing a huge shift in the expectations of teaching styles with the onslaught of the Common Core. I LOVE the new student-centered classroom as it gives students greater responsibilities and expectations of themselves; also, I no longer am required to model every basic concept because the new curriculum provides scenarios for the students to make their own meaning. Furthermore, it encourages instruction on self-monitoring strategies and alternative methods of reaching outcomes – tools that students will use throughout their lives as successful learners and adults of the 21st century workforce. In Learning Theories and Instruction, a course text I’m reading for an instructional design degree I’m working on, Ormrod, Schunk, and Gredler made the same recommendations to increase retention and transfer. Thank you for allowing me to dig through your blog and apply what I can to my little learners! Can’t wait to graduate and apply it to the adult workforce as well!

References

Ormrod, J., Schunk, D., & Gredler, M. (2009). Learning theories and instruction (Laureate custom edition). New York: Pearson.

By the way, a large chunk of my class has been singing your praises on our blogs – a new thing for me but a required part of our course work. Feel free to check it out on the above website! Thanks again!

Hi Cathy,

You make a good argument for putting information first when trying to help people learn. I know that I find it very comforting to know the basic framework when it comes to learning. It not only allows my mind to relax, but it also helps prevent those distracting thoughts about what is going to happen next.

While designing the learning environment to fit a classroom might ease the need for a control freak, there may be times when you need a control freak. Take, for instance, the Civil War. Riots broke out in New York over people being drafted about a war they had no interest in fighting (History). However, if Abraham Lincoln hadn’t forced all those deaths, slavery may not have been abolished and we might never have seen the equal rights amendment passed.

Is there a time for a control freak? I don’t think any amount of preparation could lead people who didn’t necessarily believe in your cause to fight for your country. How is one supposed to make people do or learn something without force if they refuse to be reasonable?

On the other hand, maybe this justification is taking things too far. Many people use the argument that children need to be forced to comply, but maybe all we do by “controlling” them is teach them that right means following instructions? The general rule tends to be that people in authority are rarely happy with resistance with their wishes (Lisbe, 2008). This is something that is impressed upon us at a very young age, and even now is an important concept to understand in order to find employment. When people hire you to work, they expect you to do what they tell you to do, or they will find someone else.

We all have to eat, and if our very survival depends on our ability to obey, is allowing someone to control you really a bad thing? Maybe it is, if following such control ultimately lead things like the Holocaust? Is there a balance, and where can it be found?

Ultimately, I think that although winning people over engaging thought and productive design techniques is ideal, there are still instances where people need to be controlled.

Aren’t laws really for the lawless (Bible), for those who put their own needs over those of the group? Maybe there isn’t any real right decision, but instead a chance to apply your best guess and wait on a higher authority on the outcome?

Jamie

References:

History. (n.d.). The Draft in the Civil War. United States History. Retrieved from http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h249.html.

Lisbe, E. (2008). Don’t You Sometimes Have to Force Children? Lisbe Partners. Retrieved from http://lisbepartners.com/content/view/forcing-children.html.

Bible. (n.d.). 1st Timothy 1:9. Biblehub. Retrieved from http://biblehub.com/1_timothy/1-9.htm.