Here's a summary of what I presented at the January 2015 Learning Technologies conference in London, along with links to lots more detail.

My point

The building block of a scenario activity is the scenario question. Unfortunately, it's easy to write a bland scenario. To write thought-provoking scenario questions, we need to:

- Make sure a scenario question will be useful.

- Answer not only "What do they need to do?" but also "Why aren't they doing it?"

- Work closely with the SME to identify the common mistake, other popular but poor options, and the best choice.

- Write a vivid yet subtle stem (question) that puts the learner in a realistic context. Everything else depends on a strong stem.

- Write options that take advantage of cues put in the stem.

- Prefer feedback that shows the result of the choice and lets people draw a conclusion on their own.

- Plunge learners into the activity without first presenting everything they need to know. Include optional information in the activity and show it during feedback.

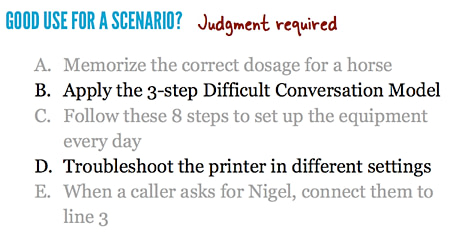

When is a scenario question useful?

Consider writing a scenario if all of the following is true:

- You've determined that training really is part of the solution. See How to kick off a project and avoid an information dump and Is training really the answer?

- You and the SME have listed specific, observable behaviors that are required to meet the client's goal. See Why you want to focus on actions, not learning objectives.

- For each behavior, you've asked, "Why aren't they doing it?"

- The behavior for which you're considering a scenario requires judgment, not just a regurgitation of facts or blind obedience to a process.

What should I do with the SME to prepare?

- For each behavior, ask for concrete, specific details about the context, the most common mistake, other mistakes being made, the correct response to the challenge, and what would realistically happen as a result of each choice.

- If your SME is having trouble being specific, ask them to tell a story about a time when they or someone else performed the behavior in question with a memorable result, and then review the story with them to ask for more detail.

- Ply your SME with donuts, coffee, chocolate, or whatever it takes.

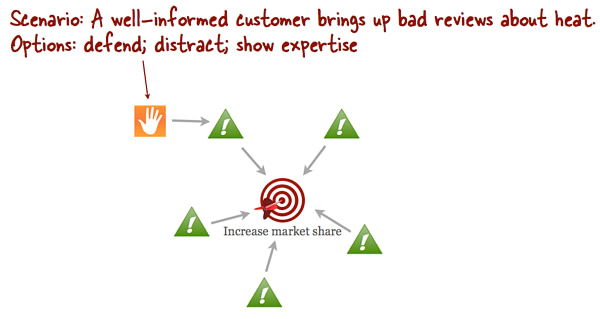

In this example, which shows the beginning stages of an action map, the SME has said that salespeople often get defensive when presented with an objection about the widget's heat. They also might (incorrectly) try to distract the customer with a cooler and probably more expensive widget. What they really should do is show that they know the entire world of widgets and aren't afraid to talk about concerns.

The stem and options

If you take the time to write a detailed, subtle stem, you enjoy the following happy results:

- It will be much easier to write non-obvious options.

- Learners will be intrigued and challenged.

- Learners will feel like you respect their intelligence and know what they face on the job.

Before you write, don't forget to answer these two questions for the behavior:

- What do they need to do?

- Why aren't they doing it? (especially consider challenges created by the context)

The following stem is a draft that participants and I wrote in one of my workshops. It focuses just on what midwives in African villages need to do (put a pre-term baby directly on the mother's chest; don't wrap it separately). When we wrote the draft, we had trouble thinking of more than two options.

Your patient has just given birth. You've cleaned the baby and weighed it. It weighs four pounds. What do you do next?

A. Swaddle the baby with a clean blanket to keep it warm

B. Put the naked baby on the mother's naked stomach

When we added the context of the birth -- including the pressure from relatives to use local traditions -- we wrote a richer stem and immediately came up with many more options. By adding context, we added the complexities that require the midwives to use judgment, not just follow a simple rule. (This is still just a draft to show the SME.)

Your patient, a shy young woman named Mary, has just given birth to a four-pound boy. Mary's aunt reaches for the baby with joy.

"He's so small!" she says. "Let me wrap him!" She indicates the handmade blanket she brought, smiling.

What do you do?

A. Wrap the baby in the blanket and put it on Mary's stomach so it has contact with her.

B. Help the aunt swaddle the baby so it's done correctly.

C. Say, "Actually, the baby will be warmest on its mother's stomach. Let me show you."

D. Ask the aunt to go for some more warm water and put the naked baby on Mary's stomach when she's out of the room.

E. Say, "Swaddling is our old way, but mothers in Village X have found the baby is happiest on the mother's stomach."

The rewrite still tests whether midwives know that a four-pound baby shouldn't be swaddled. But it also lets them practice applying this knowledge in a difficult context.

In the rewrite, we also followed these guidelines:

Some techniques from interactive fiction (the Noah and Brian example) can help you provide a rich backstory.

Feedback

The "show, don't tell" recommendation applies here, too.

Telling feedback interrupts the story and shortcircuits our brain. Instead of letting us draw conclusions, it just tells us what to think:

Incorrect. By accepting the watch, you've encouraged Mr. Bribesalot to think that you're open to larger gifts. Even though the watch is just a cheap toy, officials with a history of corruption like Mr. Bribesalot often misinterpret the acceptance of small gifts as a willingness to consider larger ones.

In contrast, showing feedback continues the story without interruption. It treats learners as the adults they are, letting them draw conclusions on their own:

"I'm delighted you like the Hello Kitty watch!" Mr. Bribesalot says. "I myself am also a very big fan of Hello Kitty. I even have a Hello Kitty private plane. For our next meeting, let's meet in my plane! I can show you our beautiful countryside as we discuss our collaboration, and then we can enjoy a fine steak at my country retreat."

If your audience consists of beginners or you're convinced that they can't be trusted to draw conclusions from "showing" feedback, include "telling" feedback as well. Consider making it optional: First "show" the result of the choice without interrupting the story, and include a "Why did that happen?" button to display optional "telling" feedback.

Information

Most training, regardless of its format, feels like a long presentation interrupted occasionally by an activity, often a quiz. Instead, I recommend that we make the training feel like a stream of activities, and include the necessary information in the activities.

For example, in a course to reduce needlestick infections, we could skip the list of do's and don'ts and just plunge learners into an activity. There is no information presentation before the question shown below. The information that they need is linked at the bottom, and it includes a copy of the real-world job aid that's hung on the wall of every examining room and that Magda could look at right now.

Because this information is optional, learners with experience or too much confidence can make choices right away. Others will look at the information first.

The feedback continues the story (Magda gets hepatitis C) and shows the information that the learner should have looked at. A fat arrow points to exactly what they should have done.

If you include the information in all feedback, both correct and incorrect, you answer one of the most common concerns of stakeholders: "We have to make sure everyone is exposed to all the information!" If you design realistic activities and include the required information in the feedback for all choices, anyone going through the activities will be "exposed" to all the information. They'll also be far more engaged than they would have been in a presentation.

For research supporting this approach, see Throw them in the deep end!